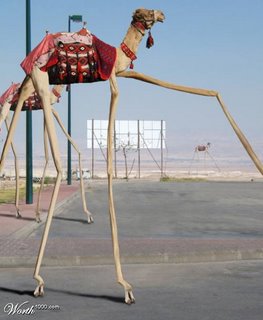

In the RP's honor, this image of Dali Camels by Pixelmasher done for a Worth 1000 photoshop contest.

In the RP's honor, this image of Dali Camels by Pixelmasher done for a Worth 1000 photoshop contest.Editor's NOTE: This post was ready way earlier, but Blogger vomited and I couldn't post it until now.

I am going to miss The Religious Policeman, the Saudi ex-pat living in the UK and giving the poop on life in the kingdom. I found his posts as heartbreaking as funny when I came to realize how little he has to embellish to create what sounds like the broadest satire. However, he's quitting his blog, which he notes has 400 posts one may yet read at leisure daily until 2007, in order to clear the time to write a novel with a collaborator he met in the blogosphere. Good for him.

Sure, I could quit blogging to get all disciplined about noveling, too, but I think it sends the wrong message... to the kids.

As apostropher kindly sent me the full text pdf of B.R. Myers' 2001 article in The Atlantic Online that I referenced here (item 5), I went ahead and read the darn thing, 21 pages which were pointed, concrete, and demand another reading, unlike his subject matter, IMHO.

The dualism of literary versus genre has all but routed the old trinity of highbrow, middlebrow, and lowbrow, which was always invoked tongue-in-cheek anyway. Writers who would once have been called middlebrow are now assigned, depending solely on their degree of verbal affectation, to either the literary or the genre camp. David Guterson is thus granted Serious Writer status for having buried a murder mystery under sonorous tautologies (Snow Falling on Cedars, 1994), while Stephen King, whose Bag of Bones (1998) is a more intellectual but less pretentious novel, is still considered to be just a very talented genre storyteller.

It was refreshing to read Myers castigating the stylistic blecchs of Don DeLillo and Cormac McCarthy, but first, Annie Proulx:

Like so much modern prose, this demands to be read quickly, with just enough attention to register the bold use of words. Slow down and things fall apart..."Furious dabs of tulips stuttering in gardens." "An apron of sound lapped out of each dive." ... In one brief paragraph in The Shipping News a man's body is likened to a loaf of bread, his flesh to a casement, his head to a melon, his facial features to fingertips, his eyes to the color of plastic, and his chin to a shelf... Today anything longer than two or three lines is likely to be a simple list of attributes or images. Proulx relies heavily on such sentences, which often call to mind a bad photographer hurrying through a slide show.

Myers identifes the overwording and illogic, the use of the laziest of descriptions in quantity to draw a perimeter around an idea. Evocative, perhaps, and that's a term I often lazily use myself, but it isn't at all the same as communicating, hitting it between the eyes on the first shot. Instead, it's a gesture-drawing style of writing or like playing charades with concepts, miming several inapt fascimiles in succession until the reader nods and says, "I got it."

A more concise syntax would show up the poverty of this description at once, but by stringing a dozen attributes together she ensures that each is seen only in the context of a dazzlingly "pyrotechnic" whole.

Myers identifies the same tendencies in the "muscular" prose of Cormac McCarthy.

The reader is meant to be carried along on the stream of language. In the New York Times review of The Crossing, Robert Hass praised the effect: "It is a matter of straight-on writing, a veering accumulation of compound sentences, stinginess with commas, and a witching repetition of words ... Once this style is established, firm, faintly hypnotic, the crispness and sinuousness of the sentences ... gather to a magic." The key word here is "accumulation." Like Proulx and so many others today, McCarthy relies more on barrages of hit-and-miss verbiage than on careful use of just the right words.

Further, Myers criticizes the vague allusions to big ideas without elaboration and the shorthand description by brand names he finds questionable in Don DeLillo's work and which I've harangued upon in less critically adored writers like James Patterson. He extracts examples of the "sluggishness" of David Guterson's prose in Snow Falling on Cedars. Throughout, Myers highlights what's imprecise, pointless, indulgent, bulky, and repetitive. And the article might remain a parsing of excerpts by an attentive contrarian unless such characteristics were indeed the fundament (you may decide how I mean this) of modern writers and writing's most-lauded style.

I've always found incautious repetition boring as well as slightly insulting, but I hadn't bothered to read these darlings closely enough to realize how much that's what makes my eyes roll back in my head when considering "modern literary fiction." It reminds me of conversations with people whom I meet at parties, and I'm a terrible attendee because of my habitual failing. When people bring up subjects that seem important, they often expect to toss off a popular-consensus phrase and move on while all smile knowingly, the high-five of the non-athletic.

I always fall for it though. I make the mistake of thinking they actually care about the subject and begin unintentionally bringing up facts or arguments that reveal how thin their knowledge and interest really is. Then, we both feel like jerks, because I didn't realize it was just a time-waster meant to convey a personal image without substance, a display of plumage not passion. That's how I find much of modern writing. By the time I dig in, I'm disappointed, and I think the authors would find me a poor reader who doesn't fathom that I'm not supposed to expect the well-crafted, unpatronizing, or recognizably human. Still, I am not bereft. Myers, too, considers how different this current crop is compared to past masters like Nabokov, who never wasted a reader's time with fuzzy inaccuracy and glib throwaways (emphasis mine):

When DeLillo describes a man's walk as a "sort of explanatory shuffle ... a comment on the literature of shuffles" (Underworld), I feel nothing; the wordplay is just too insincere, too patently meaningless. But when Vladimir Nabokov talks of midges "continuously darning the air in one spot," or the "square echo" of a car door slamming, I feel what Philip Larkin wanted readers of his poetry to feel: "Yes, I've never thought of it that way, but that's how it is." The pleasure that accompanies this sensation is almost addictive; for many, myself included, it's the most important reason to read both poetry and prose.

Is saying "Ditto" too lowbrow?

5 comments:

Thank you for this - a fascinating article and commentary. So glad I've chanced on your blog.

sorry, that was me - didn't mean to be anonymous.

I appreciate the kind words and- thematically speaking- that your first name is not obliquely, but precisely, like my own.

ok clare, so give it to me straight:

how do you feel about hammett, then? i think he's in the serious writer camp, myself, because of his interesting balance between creative simile and fierce allegiance to the rhythyms of american speech.

while not a master of the first line, "poisonville" aside, maybe, and while "hard-boiled" is tired, the stuff that comes out of his characters mouths seems real somehow.

on the other hand, i might disagree with you about cormac mcc. i think his best book is child of god. have you read it?

Fortune- you may have posted this eons ago, so I apologize for the late response.

Hammett is a master, as seems to me, and gains some exemption- as all groundbreakers do- for blazing a stylistic trail.

I've not read Child of God and don't know where it falls within McCarthy's writerly evolution. I freely admit it may not deserve these kind of indictments. However, Myers himself comments on the constrast between McCarthy's late and early writings, saying about an excerpted sentence from the first page of The Orchard Keeper(1965):

"There's not a word too many in there, and although the tone is hardly conversational, the reader is addressed as the writer's equal, in a natural cadence and vocabulary. Note also how the figurative language (like

something seen through bad glass) is fresh and vivid without seeming to strain for originality."

Post a Comment