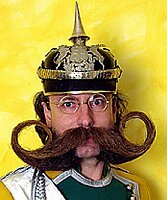

Jurgen Burkhardt is a frequent Imperial or Kaiser class winner. See item 6.

Jurgen Burkhardt is a frequent Imperial or Kaiser class winner. See item 6.1) My pal April and I will surely miss the noble Taurus line now that Ford's stopping production. We both had well-traveled, well-loved versions that gave yoeman service. Ave Atque Vale-

2) This story about a prosecutor removed from a case that's too similar to her recent, self-published novel, and the politically-motivated extraction of juicy bits from aspiring Senator Jim Webb's military thrillers are making me think about the hazards to reality-based careers of one's fictional imaginings. I'm not saying it should be a hindrance. Even Honest Abe turned his hand to the mystery form. This article has a great, if not up-to-this-moment, history of the legal thriller, most often written by lawyers for obvious reasons. However, if Webb really does identify himself as a "writer first", does that connote to the same set of skills expected from an effective politician? Based on myself and the fictioneers I know, I'm not so sure.

I think Lori Andrews may have the best combination of these careers. Be a professor, not directly accountable to public opinion, retaining access to the latest papers and experts, and perhaps able to take a sabbatical if the writing's going poorly. Of course, CVs can't tell you whether the book will be good.

3) I'm afraid it might be bad karma to bag on things I don't like. And I'd prefer to point to the wonderful. But not long ago, I finished reading such a topically-related book from my Bouchercon freebie bag. It's a legal thriller with a distinct POV on the death penalty (anti). Okey-dokey. This author was originally with a much smaller press, and this manuscript got picked up by St. Martins, very big wheels in crime fiction. The advance copy's got lavish praise blurbed on front and back covers as well as inner-page love letters from people who want me to know that this guy is the NEXT BIG THING. So I read it. I found it strikingly, remarkably poor both in characterization and plotting. By the end, it had turned into such a convoluted mess, I was actually angry about how bad it was.

It started ine with the events leading to the actual case in question, but then kept flashing back to the childhood of a character I hadn't met yet, so I sure as shootin' didn't care to be repeatedly derailed from the exciting stuff. You might then assume that this childhood stuff would distinctly impact the later events. Maybe, sort of. But it's main purpose was only to explain connections between characters which could've been done better in real time. To me, it was all expendable. A major character in the second half shows up as if we'd know she was a major player in the childhood scenes. But she's barely there. Odd for a "best friend." But then again, this book's relationships are melodramatic and overstated in general. As in, declarations of love usually mean someone's about to get shot. That transparent device actually happens more than once. The characters ping back and forth between thin motivations designed purely to advance improbable plot lines, and by killing the main sympathetic character halfway through (although remaining hazy on whether he's a borderline retarded railroadee or a saintly, love interest-eeks), the author also executes our reason for following the story.

For the writer, a lawyer himself, the most fascinating tale's probably the rich lawyer with an ethical crusade who shacks up with an entire posse on a rented ranch, transported by bulletproofed Benz costing more than $100k. Now, he's using his accumulated wealth and connections to squeeze the powerful fat cats for the right reasons. I found his machinations simplistic and tiresome. And his portrayal as a lonely moral actor after apparently spending an entire career with his conscience on mute wasn't convincing as much as wishful aggrandizement. This author's not alone. Other such writers also tend to regard their hero lawyer as messianic, regardless of how their actions and personalities might tarnish the halo in the eyes of someone who didn't pass the bar. To me, the story's always about the characters who readers feel most strongly about. The handsome, fit, well-sexed multi-millionaire might be the one I'm supposed to care about because of a misassigned nickname that doesn't fit. But he's soggy cardboard, his girlfriend's vapor, his herd of acolytes weirdly devoted, and no amount of flashback can change it. If this thing becomes an enormous hit, I'll rant against it by name and title.

Until then, I shake my shame-shame finger at St. Martins, and say that no matter how compelling one's expertise, a novel still flops if it neglects the basics of storytelling.

4) Additionally, despite relevant backgrounds and all their research, novelists may still get their real murders wrong, such as now convicted wife-killer Michael Peterson, who's declared bankruptcy (boo-hoo) and failed in his latest appeal.

5) If you're a drunk or depressed, could a strenuous spanking be all you need?

6) I'm delighted that the Handlebar Moustache Club simply exists, much less thrives.

No comments:

Post a Comment